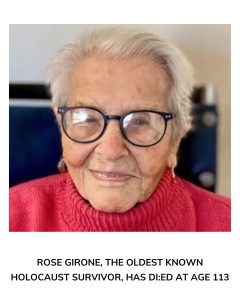

Rose Girone, the world’s oldest known Holocaust survivor, who endured both Nazi and Japanese oppression and went on to live for more than eight decades after World War II, has passed away at the age of 113. Her daughter, Reha Bennicasa, confirmed the news of her passing.

Recognized as the oldest living Holocaust survivor by the New York-based Claims Conference, which facilitates compensation for Nazi victims, Girone spent her later years in Bellmore, New York, where she passed away in a nursing home on Monday.

Born Rosa Raubvogel in 1912 to a Jewish family in southeastern Poland, then under Russian rule, Girone later moved to Hamburg, Germany, as a child. In 1937, she married Julius Mannheim, a fellow German Jew. However, when she was nine months pregnant, the Nazis deported her husband to Buchenwald, one of Germany’s most infamous concentration camps. She recounted in a 1996 interview with the USC Shoah Foundation that a Nazi officer initially intended to arrest her as well but was dissuaded by another soldier who pointed out her pregnancy.

Shortly after, in 1938, she gave birth to her daughter, Reha. Due to restrictions imposed by the Nazi regime, Jewish parents were only allowed to choose names from an approved list, and she selected the only one she liked from that list.

Determined to reunite with her husband, Girone discovered that a relative in London could assist in securing exit visas to Shanghai, one of the few places still accepting Jewish refugees. With a visa obtained through indirect connections, she was able to secure Julius’s release from Buchenwald. However, they had only six weeks to leave Germany and were forced to surrender all their valuables before departing.

Upon arriving in Shanghai, the family believed they had escaped persecution, only to find themselves in yet another dire situation. As Japan continued its military campaign in China, Jewish refugees were forced into ghettos, where they lived under strict surveillance. Girone, her husband, and their daughter moved into a cramped space under a staircase in an apartment building that had formerly served as a bathroom. Permission to leave the ghetto was granted only by a Japanese official who referred to himself as “The King of the Jews.”

To support her family, Girone took up knitting, a skill she would practice throughout her life and later credit as a source of resilience. Her daughter, Reha, told CNN that despite the immense hardships they faced, her mother remained strong and determined. “We were lucky to escape both Germany and China alive, but my mother was incredibly resilient. She could withstand anything.”

After the war, the family immigrated to the United States, where Girone continued to work as a knitting instructor. Settling in the New York area, she eventually opened a knitting store in Queens. Her first marriage ended in divorce, and she later remarried Jack Girone.

Reflecting on her survival, Girone believed in finding hope even in the darkest times. “No situation is so terrible that something good cannot come from it,” she once said, adding that her experiences left her fearless and confident in her ability to overcome any obstacle.

Her daughter echoed this sentiment, stating in an interview with the USC Shoah Foundation, “Through my mother’s example, I feel ready to face anything.”

Today, approximately 245,000 Holocaust survivors remain, with around 14,000 residing in New York, according to the Claims Conference. Girone’s extraordinary journey serves as a testament to resilience, survival, and the enduring human spirit.